|

| Edged out: Terracotta icons of the hounds

of the hunt in a Kodagu grove |

As the ka law kyntanks in the

undulating hills of Meghalaya experience minor ripples of change, the sacred groves or devarakadus

in the Western Ghats of Karnataka are caught in a whirlpool of a transforming world.

In this area, where patches of forest

stand out among coffee plantations and paddy-fields, are found ancient shrines comprising

solitary stones, terracotta icons and miniature tridents (trishul) placed under

canarium or garcinia trees, which are endemic to the region. These groves, with their own

rites and ideologies, are facing a rapid cultural and economic onslaught that seeks to

overturn the traditional way of life.

Each year, the Soliga tribals of the B R

Hills in Chamrajnagar district celebrate the roti habba festival dedicated to

Shiva. On that day, members of the community dress up in their finest and trek a steep

rocky path braving elephants, gaurs and snakes to reach the Chikka Sampige sacred grove,

which is 15 km from the Karnataka–Tamil Nadu highway. Once there, they prepare ragi

rotis and pumpkin curry, which they offer to the deity. After that, they dance and

frolic till the early hours of the morning. Once the ceremony is over, the grove is

forgotten till the next year.

The unique festival of roti

habba has survived for decades. But sacred groves are fast losing their relevance in

the societal fabric of several communities, such as in Kodagu district. They are regularly

encroached upon and converted into plantations, agricultural fields or homesteads. Old

ways are giving in to the new. Mismanagement by political regimes have also had devastating results. regimes have also had devastating results.

Whose groves are these anyway?

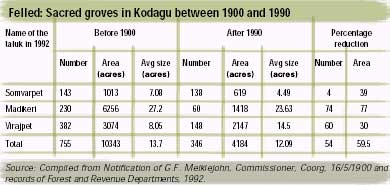

The first ever survey of sacred groves in Kodagu was conducted in

1873, when 873 groves covering 4,398.79 ha were listed. Under the then The Indian Forests

Act, 1875, these were declared as "protected forests". An 1898 report compiled

in the office of the Commissioner of Coorg (Kodagu) states that the sacred groves or devarakadu

then comprised 6,275.081 ha out of 45,0118.3 ha of total forest land.

In 1905, the ownership of the Kodagu devarakadus

changed hands and went to the Revenue Department. This transfer of ownership came at a

heavy price. According to anthropologist M A Kalam, between 1905 and 1985, the extent of

sacred groves in Kodagu had shrunk to just 2406.768 ha. In other words, a whopping 42 per

cent of sacred grove area was lost in just 80 years. In 1905, the ownership of the Kodagu devarakadus

changed hands and went to the Revenue Department. This transfer of ownership came at a

heavy price. According to anthropologist M A Kalam, between 1905 and 1985, the extent of

sacred groves in Kodagu had shrunk to just 2406.768 ha. In other words, a whopping 42 per

cent of sacred grove area was lost in just 80 years.

Although the government returned the

groves to the Forest Department under the Indian Forest Act, 1927, the battle between the

Revenue and the Forest departments continued, as each claimed the devarakadus for

themselves. In 1956, the province of Kodagu was merged with the state of Karnataka.

Finally in 1985, the Revenue Department formally handed over the ownership of devarakadus

to the Forest Department and the devarakadus were declared as reserve forests under

sections 4, 17 and 26 of the Karnataka Forest Act, 1963. But most of the damage had

already taken place by then (see table: Felled).

In 1987, the Karnataka state

government ordered that the Forest Department allow the felling of timber in devarakadu

areas only if the wood goes towards renovating the temple to which the grove is attached.

This order remains in force.

Change of address: Temples like this one in the

Hebbale sacred grove can signify more than just a new residence for the gods, they are the

result of changing social dynamics |

|

A survey conducted by the Department of

Ecology, Environment and Forests, Government of Karnataka, in the early 1990s found that

45 per cent of the groves had been reduced to less than one acre. A more acceptable figure

would be 2,550 ha or 2 per cent of the total forest cover of the state, as stated by

Claude Garcia.

Veneration of the gods and spirits has

certainly not protected the forests they reside in. According to Jeevan Chinnappa, Kodagu

correspondent for the national daily, The Hindu, "Influential people

encroached the sacred grove lands 15-20 years ago and converted them into coffee

plantations. Today these lands have been regularised." But this is not a recent

phenomenon. Before 1956, when Kodagu became part of Karnataka state, sacred groves were

often declared paisari land, de-notified for plantation or housing.

Old faith, new gods

Just as the forests of India have never remained pristine or isolated, the societies

living within them have to engage with new dynamics and economies, very often to their

detriment. Besides their spiritual significance, sacred groves also act as tools to

ascertain local identity. Devarakadus are an integral part of Kodava culture. It is

what sets them apart. It is this cultural identity that may be at stake.

The Kodavas are the dominant community in

Kodagu. The head of a Kodava family is appointed as deva takka or head of a local

temple. "Legend has it that the goddess identified one family in the village to take

care of the well being of the tribals," says C G Kushalappa, professor, Forestry

College, Ponnampet, Kodagu. However, the role of the takkas is confined to

organising the annual festival. "Management of the forest has never been given any

importance. They only provide space for our gods and there has been no ecological reason

for preserving small patches of forests," says Padeyanda Shambu, takka of

Kaykad devarakadu, Virajpet, Kodagu.

|

Change of guard in

the Manilayappa grove:

Numerous devarakadus were converted into plantations or housing colonies by the paisari

system. Others have been simply encroached upon |

Besides organising festivals, the takkas

have to provide for the well-being of the community priest. Kala Kuruba, the priest at

Hebbale devarakadu in Devapura says " The deva takka of the Hebbale deverakadu

has given me two acres of land to cultivate and make a living. Besides this, I get Rs

1,000 from the takka every year for performing the rituals during the

festival."

To some extent, the sacred groves

festivals in Kodagu are witnessing a process of culturalisation by which upper caste

communities have adopted traditional "lower caste" practices. Kala Kuruba, the

old priest of the Hebbale sacred grove, says, "During the kundi habba

festival, the Kuruba tribals clean our temple premises. Then we offer fowl and toddy (a

local alcoholic liquor) to the god Ayappa and abuse him. This way, we rid our minds of all

evil thoughts." However, there are greater instances that show the widespread effects

of a new transformation. While earlier, human sacrifice was a common feature during the

sacred grove festivals, today, these practices have been replaced with animal sacrifice.

In some sacred groves, such as the Suggi devarakadu in Somvarpet, even animal

sacrifice is strictly forbidden. Kalam calls this a conscious attempt to

"vegetarianise the deities in order to Sanskritise them" and bring them to the

fold of Hinduism. In the Suggi grove, even a person who has just eaten meat is not allowed

inside. It is said that anybody defying this rule is stung by bees.

| Upwardly mobile: A priest in the Kaykad devarakadu in

Virajpet |

|

The influence of Hinduism has led to the

construction of large, imposing temples with Brahmin priests and Hindu gods and goddesses

within the sacred groves. By definition, sacred groves have been reduced to temple groves.

Importance is given to the temple itself. From temple groves to a temple is just a step

away.

Kushallappa says, "We have to

accommodate such changes because we have evolved from nature worship to a structured

worship. However, it cannot be ignored that in modern times, conservation for its own sake

is gaining importance and the groves provide the space to fulfill this need".

One such instance is the Bhadrakali

sacred grove in Hudikere. It has got a facelift. A newly painted blue temple has replaced

an old run down shrine. This is a sign that the community has finally taken the

responsibility of managing the shrine and the Australian Silver Oak grove contributed by

the Forest Department under its renovation programme.

In a bid to revive the tradition of

sacred groves in Kodagu, a Devarakadu Thakka Mukhyastra Vedike (Sacred Groves Federation)

was formed in 2002, chaired by the conservator of forests. The vedike programme draws

heavily from traditional management practices, along with existing state forest and Joint

Forest Management (JFM) policies. However, it is not authenticated by the state

government.

| Uttara Kannada –

commercially sacred  The tradition of sacred groves is not limited to

Kodagu. In Uttar Kannada, sacred groves or kans proliferate though in varying

stages of degradation. In Uttara Kannada, people lost their rights over the kan

forests as early as in 1800, when the British took over the area. The tradition of sacred groves is not limited to

Kodagu. In Uttar Kannada, sacred groves or kans proliferate though in varying

stages of degradation. In Uttara Kannada, people lost their rights over the kan

forests as early as in 1800, when the British took over the area.

In the neighbouring Shimoga district, they were taken by the government and leased out

to the landlords. They were recognised as a separate management system until the 1960s. In

2001, the kans of

Shimoga were declared as minor forests or state forests or revenue forests, whereas in

Uttara Kannada, they were declared as protected forests or revenue forests depending on

the lands they were on. the kans of

Shimoga were declared as minor forests or state forests or revenue forests, whereas in

Uttara Kannada, they were declared as protected forests or revenue forests depending on

the lands they were on.

Thus, in comparison to Kodagu, where the Forest Department has recognised the existence

of sacred groves, the kans of Shimoga, Chikmaglur and Uttara Kannada have not been

able to secure such a status. Yogesh Gokhale, research assistant, Centre for Ecological

Sciences, Indian Institute of Sciences, says, "The kans have been referred to

as the historical sacred forests as people continue to have faith in the deity, but this

sacredness could not be protected from larger commercial interests".

The kans contribute to 5.85 per cent of the total land use in Uttara Kannada. In

some cases they are found on the soppina betta (leaf manure forests) lands, which

are also owned by the forest department but managed by individual families. They are also

found associated to the hakkal bena (agricultural fields).

The sanctions on extraction from the kans are very flexible. The people in

Shimoga and Uttara Kannada can tap toddy, honey, gum, cultivate pepper and collect leaves

for manure from the kans. As utilitarian lands they cater to the needs of the

villagers. However, the kan holder has no permission to plant coffee. Between 1966

and 1985, a number of kans were converted into acacia auriculiformis plantations by the

forest department. |

|