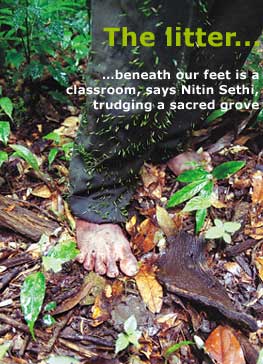

We

are plodding barefoot on a thick, moist carpet of leaves, twigs and thorns that bite and

snap at our feet. It is mid-morning on a September day. The monsoon clouds above still

seem to have a shower or two to shed on the rolling hills and forests of Meghalaya. It is

only the thick wad of forest litter that prevents us from slipping on the rain-damped

loamy soil underneath. We are in a sacred grove in Raliang village, roughly 25 km

northeast of Jowai, the biggest town in the Jaintia Hills district. "This is one of

the best preserved sacred groves in Meghalaya," says Krishna Upadhyaya. He should

know. He recently completed his PhD at the North East Hill University, Shillong. His

thesis was on the flora of this grove. We

are plodding barefoot on a thick, moist carpet of leaves, twigs and thorns that bite and

snap at our feet. It is mid-morning on a September day. The monsoon clouds above still

seem to have a shower or two to shed on the rolling hills and forests of Meghalaya. It is

only the thick wad of forest litter that prevents us from slipping on the rain-damped

loamy soil underneath. We are in a sacred grove in Raliang village, roughly 25 km

northeast of Jowai, the biggest town in the Jaintia Hills district. "This is one of

the best preserved sacred groves in Meghalaya," says Krishna Upadhyaya. He should

know. He recently completed his PhD at the North East Hill University, Shillong. His

thesis was on the flora of this grove.

Before we arrived, Upadhyaya had told us the first thing to do upon reaching the village is to seek an audience with the doloi or king of this elaka comprising 66 villages. No one can enter the grove without his written permission. The doloi turned out to be young, unaffected and rather austerely dressed for his royal rank. We found him sitting behind a wooden desk in a dimly-lit room, which was an exercise in frugality, made of reinforced concrete cement, typical of a hill village enjoying some "fruits" of development. Our conversation was terse. Upadhyaya, our guide, was not well-versed with Khasi language, and the doloi seemed uncomfortable in English. Ours was a team of six — Upadhyaya, the grove’s priest Chavas Lyngdoh, our photographer Surya, another villager, our very intrigued taxi driver, and I.

Unlike national parks and sanctuaries, where the thick core is kept isolated from human settlements, the boundaries of this sacred grove begin right at the edge of the rice field behind the doloi’s house. The Khasi locals call this 30 ha grove Khlaw Blei, home to the god U Ryngkew U Basa. At the edge of the forest, Upadhyaya reminded us, "We have to take our shoes off. The forests have to be walked barefoot." Walking barefoot through a patch of undisturbed subtropical mixed leaf forest can be a very unnerving experience. Even more so with Upadhyaya constantly chipping in with his knowledge of the various snakes and rodents that flourish in the thick undergrowth. But we took off our shoes and entered. As we struggle to find our way through the vines and stragglers, Upadhyaya tells us about the taboos that hold the forest together — "Nothing is ever removed from the grove. Not a twig, not a fallen branch can be taken out. No tools or implements are allowed inside except with the priest or lyngdoh. They do not want to anger the god U basa." This small patch of forest houses rare botanical gems and has a high faunal diversity. Under the thick canopy, where the very lack of sunlight ensures that photography is a formidable challenge, reside plants that at times have less than five specimens left in the entire forest. Between 48 and 53 per cent of the plant species here are classified rare, some of them rediscovered after more than three decades. In the course of his thesis, Upadhyaya had found more than 450 individual specimens of 80 plant species in just 0.5 ha of forest — a goldmine of information for a biologist! Not surprisingly, he can barely hide his excitement at being in the forest for one more time, even after spending nearly three years here. Yet he is cautious. "I nearly lost my life twice in this grove to snakes. This is the most dangerous grove I have ever visited." Meanwhile, the lyngdoh frisks around with ease. He is at home with the thistles, the weeds and the infinitesimal insects that attack even a millimetre of exposed skin. He runs down a hill to pluck a leaf, which he tells us excitedly is used for a particular ritual. A little later, he plucks another one that is routinely used in local cuisine. The forest is indeed a relic. And the unassuming lyngdoh is its curator. In his thesis Upadhyaya claims that this 30 ha grove represents the ecological climax that a forest can attain in the region. Is the survival of this forest linked to the fact that buffering it is another 40 ha of forest, which is used for selective felling of trees and removal of forest litter for firewood? Can the elaka afford a sacred grove exactly because it has set aside a reasonable amount of land for other forests?

The lyngdoh is integral to the political ecology of the grove. His small frame bears the weight of a sacred history rather lightly. While we are looking for pontificating speeches on the sacred and the profane, we get a kwai (betel nut) chewing gentleman who will pose rather reluctantly for a photograph before the ancient sacrificing stones. His confused and flickering eyes betray confusion. What is this hullabaloo and flashing cameras in the sylvan darkness all about? He knows for years now the people of the elaka gather for an annual sacrifice to appease the spirits, everyone participates and prays to U basa. Is there a direct relation between the strength of the original faith that continues to flourish in Jaintia Hills and the health of the grove? Upadhyaya thinks so. We have to corroborate it elsewhere on our travels. l |

||||

|