The doctors said that this time they had caught

the recurrence so early that they were sure the 1994 treatment would get me back in

remission, but they were also certain the remission would not last even a year. I needed

something more definite, something with a higher probability of cure — “such

that you can live till 70 or beyond till only old age kills you”, as one of the

doctors who was very fond of me put it. She and others knocked their heads together and

came up with a solution: medicos in Paris were experimenting with bone marrow transplants

to cure nhl. “After we put you into remission, you must immediately go in for this

treatment,” they recommended. Bone marrow transplant is one the most invasive medical

procedures developed by modern science. I went through it in mid-1996 and hope that I have

finally gotten rid of the disease. That, however, is something that only time will tell.

Meanwhile, I will keep praying that some medical scientist somewhere, will continue to

look for a simpler, less horrifying and more definitive cure for this rare disease.

|

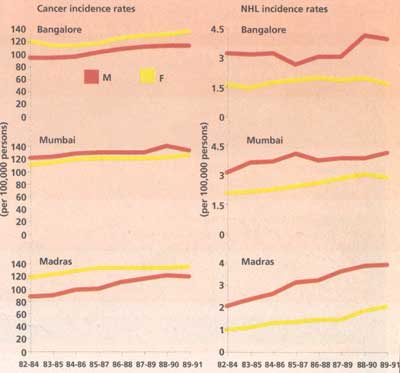

Incidental

Comparisons : Cancer and NHL Age-adjusted incidence rates and growth (bottom table) :

3-year running averages (1982-91)

|

| |

Cancer |

NHL |

| M |

F |

M |

F |

| Bangalore |

20.65% |

13.17% |

23% |

23% |

| Mumbai |

11.63% |

13.53% |

33% |

37% |

| Madras |

38.07% |

15.05% |

92% |

103% |

Incidence

of Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma is rising faster than general cancer incidence. In Madras,

it has doubled in 10 years |

People as statistics

But why should this story of an individual cancer patient be of interest

to anybody in a large and growing nation like India? Individuals are, after all, mere

statistics. My case, however, is instructive because it represents today the scale of

life-threatening and destructive processes that we are inflicting upon ourselves. My

cancer, like most other cancers, is deeply related to environmental pollution — an

issue, on which, ironically, I have written numerous articles and books, given lectures

and made films to increase public awareness of the threats we face. Therefore, I feel a

sense of moral responsibility for going on.

My cancer, like most

cancers, is related to environmental pollution

The poor, naturally, suffer more than the rich from

environmental degradation. However, at least the powerful urban middle and upper classes

— we had thought — were intelligent and self-indulgent enough to try and protect

themselves and moderate the impact of environmental destruction on their own lives. That

theory has proved to be a total chimaera. The elite of our nation have failed to

internalise the ecological principle that every poison we put out into environment comes

right back to us in our air, water and food. These poisons slowly seep into our bodies and

take years to show up as cancer, as immune system disorders, or as hormonal or

reproductive system disorders — affecting even the foetus.

One of every 10-15

people living in metros are potential cancer victims

Is it, therefore, not imperative for a society

to find a way that balances its urge for economic growth and material comforts with the

requirements of its natural and human health? Isn’t this some thing that we owe to

ourselves and to our children?

Cancer as statistics

Although cancer statistics in India — relatively poor — probably understate the

extent of the disease, what they tell us is terrifying. There are six hospital-based

cancer registries in India — five in Bangalore, Mumbai, Madras, Delhi and Bhopal and

one in the rural area of Barsi near Pune — which give us an idea of urban and rural

cancer incidence in India (see Table 1). The data shows that age-adjusted cancer incidence

rate per 100,000 people in the five urban centres varied between 101.2 (Bhopal) to 143.6

(Delhi) for women in 1990, whereas for males it was between 107.5 (Bhopal) and 138.9

(Mumbai). This incidence was twice the incidence rate of 56.2 in Barsi, which shows that

living in our polluted urban centres more than doubles our chances of developing cancer.

Table 3 A lifetime of death

Cumulative (lifetime) cancer incidence rates (0-64 years) |

| |

MALES (%) |

FEMALES (%) |

| |

1990 |

1991 |

1990 |

1991 |

INDIA |

| Bangalore |

6.66 |

6.59 |

9.92 |

9.90 |

| Mumbai |

7.08 |

6.83 |

7.79 |

8.52 |

| Madras |

7.54 |

7.68 |

9.88 |

9.85 |

| Delhi |

7.59 |

7.33 |

10.56 |

10.08 |

| Bhopal |

6.70 |

|

7.79 |

|

| Barsi |

2.97 |

2.78 |

4.88 |

5.55 |

World |

Connecticut

(USA)-White |

15.21

(1978-82) |

15.8

(1983-87) |

16.49

(1978-82) |

17.3

(1983-87) |

| Oxford(UK) |

13.15

(1979-82) |

13.1

(1983-87) |

14.10

(1979-82) |

14.7

(1983-87) |

| Finland |

12.27

(1977-81) |

13.9

(1982-86) |

10.54

(1977-81) |

13.1

(1982-86) |

| Miyagi(Japan) |

11.27

(1978-81) |

8.79

(1983-87) |

13.3

(1978-81) |

9.8

(1983-87) |

With

their worsening environmental conditions, Indian cities are headed the same way as their

counterparts in developed nations |

There is another way of looking at this data by

asking the question: what is the chance that I will be affected by cancer during my

lifetime? The answer is stunning. If you are living in one of the four metros —

Bangalore, Mumbai, Madras or Delhi — the chance of your catching cancer during a

lifetime is as high as seven-11 per cent. In other words, one out of every 10-15 people

living in these cities is going to become a cancer victim during his/her lifetime. Or,

assuming an average household size of five, it means every second to third household in

these metros will have a member falling victim to the disease. However, if you were living

in Barsi, the chances of cancer in a lifetime would go down by half — only one out of

20-36 persons will get cancer in their lifetime.

In industrialised nations like Britain or the us,

the average lifetime cancer incidence rate in the late ’70s was one out of every six

to eight persons. With environmental conditions rapidly worsening here, there is no reason

why Indian cities will not get there very soon. In industrialised nations like Britain or the us,

the average lifetime cancer incidence rate in the late ’70s was one out of every six

to eight persons. With environmental conditions rapidly worsening here, there is no reason

why Indian cities will not get there very soon.

But while cancer is an issue that impinges on

national consciousness in the West, it does not do so in India. Experts in us argue that

what is occurring in their country is nothing short of a ‘cancer epidemic’. The

concern for cancer shared by millions in the public has strongly fuelled environmental

regulations for control of air and water pollution and toxic wastes. In India, cancer is

still largely regarded as a relatively insignificant threat to public health. Yet one

conservative estimate puts the total number of national cancer cases by the year 2001 at

806,000. This figure, of course, does not include people who probably cannot even reach

hospitals and get diagnosed, especially amongst the vast population of rural and urban

poor.

In India, cancer is

still largely regarded as a relatively insignificant threat to public health

Let me look at statistics about the cancer I am

suffering from Non Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. In 1990-91, nhl was listed amongst the eight

most common forms of cancer in Delhi, Madras and Bangalore amongst males and in Delhi,

amongst females, too. But there are less than 200 medically recorded cases worldwide where

nhl has affected the eyes; I am probably the first case of ocular lymphoma diagnosed from

India.

|