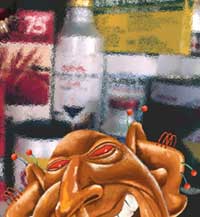

THE

BUSINESS OF POISONING

Endosulfan constitutes only a small share of the

pesticide market. So why is the pesticide industry paranoid?

The

protest against endosulfan in Kerala has become a symbol of struggle against pesticides in

India. The pesticide industry is worried about endosulfan as much as it is of its other

products. As Dave proudly puts it, "I do not defend just one molecule. I am the

president for 200 molecules. We will not ban anything just on the basis that it is banned

in other countries." If endosulfan is banned in Kerala, it could have a cascading

effect in the rest of the country. A successful campaign for banning a particular

pesticide will fuel the fire for other movements as well in India. More pesticides would

be under scrutiny. More communities would feel encouraged to protest. And more pesticides

would be on the hit list. That is something the industry cannot afford to lose out on. The

protest against endosulfan in Kerala has become a symbol of struggle against pesticides in

India. The pesticide industry is worried about endosulfan as much as it is of its other

products. As Dave proudly puts it, "I do not defend just one molecule. I am the

president for 200 molecules. We will not ban anything just on the basis that it is banned

in other countries." If endosulfan is banned in Kerala, it could have a cascading

effect in the rest of the country. A successful campaign for banning a particular

pesticide will fuel the fire for other movements as well in India. More pesticides would

be under scrutiny. More communities would feel encouraged to protest. And more pesticides

would be on the hit list. That is something the industry cannot afford to lose out on.

There are already reports

of a similar problem in Karnataka. The Karnataka Cashew Development Corporation had been

spraying endosulfan on its plantations in Dakshina Kannada and Udipi districts since 1987.

People in these areas are also suffering from strange diseases (see ‘Double

Trouble’, Down To Earth, Vol 10, No 11).

Larger

game plan

The aim of the industry's campaign is, in fact, much larger. It is to strangle all the

voices that are calling for a ban on pesticide products. Worldwide, awareness about

harmful effects of pesticides on humans as well as the environment is increasing.

Governments are buckling under the pressure from the civil society groups to ban harmful

chemicals and pesticides. Last year, Columbia banned endosulfan. The Philippines

reinstated the ban on endosulfan after a long-drawn battle with the industry (see

box: Threats and a ban). Other countries are either restricting

the use of this pesticide or banning it completely. The industry is feeling the heat for

more than one reason. Recently, India signed the Stockholm Convention, a global treaty to

protect human health and the environment from persistent organic pollutants (POPs). POPs

are chemicals that remain in the environment over long periods. By implementing the

Convention, governments will eliminate or reduce the release of POPs into the environment.

In the first phase, 12 POPs have been identified for phase out. Endosulfan is not yet on

this list, but has all the ingredients to make it in the next round.

As consumer pressure is

increasing, corporate bodies are voluntarily moving away from pesticides. "Industry

representatives told me that endosulfan for cashewnut plantations is just a small market.

They are more concerned about endosulfan being used in cotton and in other states. They

said if it is banned in Kerala, it will have repercussions all over India," says

Salam. When Dave was asked whether they felt threatened by such campaigns (like the one on

Kerala) he replied: "It's just that we have to protect our interests and present our

side of the story."

Threats and a ban

It’s not easy to take on the

pesticide industry. The Philippines knows it better |

| The

Philippines banned endosulfan in 1992. The industry led by Hoechst of Germany launched an

offensive. It filed contempt proceedings against the Philippine Fertilizer and Pesticide

Authority’s (FPA), which imposed the ban. It also harassed field workers who came

forward with their personal experiences about exposure to endosulfan. The ban was

successfully challenged by the industry. In 1993, a subsidiary of Hoechst, AG, of Germany, filed another

lawsuit against a news agency, Philippine News and Features, that ran a story on

the possible carcinogenic nature of the insecticide, Thiodan (Hoechst’s trade name

for endosulfan formulation). Even a scientist quoted in the story, Romeo Quijano, was sued

for over US $814,800, according to Pesticide Action Network (PAN), a global anti-pesticide

body.

Citizen and farmers

groups got together to fight back. They were outraged that anyone coming out in the open

about the effects of pesticides was slapped with a lawsuit. Activists were also disturbed

by media offensive initiated by Hoechst’s regional subsidiary that portrayed

pesticide products as safe.

In March 1994, the

Philippine government ordered Hoechst to withdraw its television advertisement on Thiodan

calling it "false, misleading and deceptive". On June 1, 1994, the government

reinstated its restrictions on endosulfan sales and banned triphenyltin acetate, despite

threats by Hoechst that it would pull out of the country if the decision were not

reversed. The ban still holds on the use of endosulfan, except for use in pineapple farms. |

NEXT>>>

|