|

|

| |

Water in the wells

1. The scourge of water scarcity in Saurashtra

Saurashtra was not always a water-scarce area. People say that water was easily available in the region 10-15 years ago. Ashvin A Shah, a US -based engineering consultant who conducted a survey in 1998 on water availability in the region, says, The presence of 700,000 dugwells in Saurashtra region indicates the presence of extensive groundwater aquifers throughout the region. This means there is one well for less than 20 people or one well every 300 metres"1.

Shamjibhai Antala of Saurashtra Lok Manch, who has single-handedly worked to recharge over 300,000 wells and tubewells in Saurashtra, says that the groundwater table in most areas of Saurashtra and Kachchh was about 12-15 metres below the surface till the 1960s. However, due to overexploitation of groundwater for irrigation, groundwater has been declining by an average of 2.5 m every year leading to steady intrusion of saline water2. According to G F Joshi, a government official in Rajkot, the groundwater table in these areas has fallen below even 300 metres in some parts of Saurashtra1. As a solution to the water scarcity, people have been digging deeper and deeper, going even up to 600m at which depth it is extremely difficult to recharge as these are confined aquifers2.

While cities get the attention of politicians and thus Rajkot city is now being provided Narmada water, the rural areas continue to face acute water shortages. The entire Saurashtra region had been severely drought-hit since 1985.

2 Worst drought of the century

The drought at the turn of the century in 2000-01 was one of the worst droughts of the century for Gujarat and Saurashtra was even more affected. According to the Indian Meteorological Department, the Saurashtra and Kutch regions received 42% below normal rainfall.

In September 2000, water storage in different reservoirs of the state had come down to 2 to 12 per cent, the dead storage level or the minimum storage that needs to be maintained. Reservoirs, rivers, and streams of Gujarat had all dried up and in the Saurashtra region, 113 minor and major dams had dried and only 20 per cent had dead storage level. Big cities and towns like Rajkot and Bhavnagar received water every 20 days, and Dhoraji and Upleta, twice a month. When the state finance minister was in Upleta town near Rajkot to hold a public meeting, he was driven away by angry mobs1.

3 The hydrogeology and topography of Saurashtra

The Saurashtra region is made up of a central elevated region of about 75 m to 300 m above sea level that steeply slopes down to valleys. There is no perennial river but there are a number of rivulets, which flow away from the central elevations. The region is underlain by hard basaltic rock and has very limited storage potential. The soil is also clayey in nature, adding to constraints in natural storage of water. The annual potential evapotranspiration (PET) is highest at Rajkot, with a value of 214.5 centimetres (cm), which means that the little water the region gets quickly evaporates3. The average annual rainfall for Rajkot district is 592 millimetre (mm) with only 27 days of rainy days4, which is subject to a great deal of variability. All these factors contribute to high surface run-off and little recharge. Thus, the entire region is arid to semi-arid and prone to drought.

The region suffered from severe drought between 1985 and1988 and this catalysed a movement to harvest rainwater using diverse technologies. Recharging groundwater in this region, with high surface runoff and very little secondary porosity to hold the water is a difficult task. Farmers found that even when there was rain, the rainwater flowed away and their wells remained dry. Thus, one of the earliest innovations was to channelise the rainwater into the dry wells. This was the beginning of the highly successful Well Recharging movement in Saurashtra. Others have used the method of constructing sub-surface dams below the riverbeds to create additional storage, and recharge groundwater.

4 The work of Vruksh Prem Seva Sanstha Trust in Gondal and Jamkondarna talukas

Vruksh Prem Seva Sanstha Trust had been encouraging farmers to build check dams by getting them funds for the cost of the cement from various government projects for drought alleviation since 1987. After the severe droughts of 1999 and 2000, it decided to involve the people in constructing check dams to harvest and recharge groundwater. The water level had receded to more than 150 m and there was no assurance of taking even 1 crop in a year.

In 1998, the VPSST applied for and received the first grant of Rs.10-12 lakh (US $ 20000) to undertake work in 9 villages. In the beginning, the farmers were not willing to contribute funds as they did not believe in participating in government projects. Also, the villagers were unsure and not confident in their engineering and construction skills. In order to create confidence among the villagers to participate in this task of building check dams, VPSST announced that he would begin constructing check dams using funds from the government and if the villagers find it beneficial, they could then contribute their share of the money for the projects. By the year 2000, farmers began to see the effect of the check dams – water table had increased and there was water available in the wells. This was the beginning of the participatory water harvesting movement in Rajkot district.

Between 2001 and 2007, the Trust helped to construct a series of 1605 check dams in 27 villages of Gondal and Jamkondarna talukas. In addition, the Trust also constructed underground tanks to store harvested rainwater, farm ponds and soak-pits. Since 2001, the farmers of these talukas have been able to change their crop patterns for the better and have seen a vast improvement in their socio-economic life. The community-based rainwater harvesting undertaken through check dams completely changed the lives of the villagers in these talukas. Lush green grass, brimming rivers and wells depict the success story of 27 villages in Gondal and Jamkandorna talukas of Rajkot district.

The farmers have realised the usefulness of water harvesting and are recharging the groundwater in every possible way. They have increased the height of their farm boundary, so that the water collected in the fields during rain has ample time to get absorbed in the soil. They are also harvesting their rooftop for drinking water needs. The villagers are harvesting rainwater through different direct and indirect processes.

A total of 67 dams were constructed in Mespar village of Gondal taluka and 1538 dams in Jamkandorna taluka.

In January 2008, when CSE staff visited the village of Boriya, it found that rainwater harvesting was being carried out widely and there were several households that were depending only on rainwater for their drinking and cooking needs.

|

Premji bhai Patel and Vruksh Prem Seva Sanstha Trust

Premjibhai Patel was born in a small village of Bhavyavadar in Upleta Taluka, Rajkot District. Although he was from a farming family, he took to trading in textiles as a profession and moved to Mumbai in the 1970s. However, he did not get a sense of satisfaction and wanted to contribute to the community. Inspired by a character in a play written by Manubhai Pancholi (a well-known educationist in Gujarat, who created employment through tree plantation), Premji Bhai, decided to devote his life to planting trees.

He came back to his native village Upleta, in 1987, after retirement from his job and started working in Rajkot district by distributing seeds to people for plantation. He started Vruksha Prem with the idea of popularising tree plantation.

When he saw the people of his village deepening their wells every year to meet their water demands, he became interested in the idea of harvesting rainwater. The drought of 1987 further spurred his interest and in the late 1990s, he got involved in activities of building check dams as a measure of harvesting and recharging groundwater. He used funds from the drought alleviation programmes to catalyse a movement for water harvesting and recharging in Jamkandorna and Gondal talukas of Rajkot district.

He has received a number of awards for the watershed movement, including the Santbal Award (2003), Jalsanchay Gaurav Puraskar (2003) and the Jaldhara Award (2004)5.

|

5. Construction of check dams

Premjibhai followed Bhanjibhai of Visavadar, Junagadh in designing the check dams in this region. He developed the designs of the semi circular check dam by using iron bars in construction. In the initial phase stones were placed in the flowing water keeping a little distance between two stones. Later on this gap was filled up using river sand, stones and cement. The work started with the villagers digging out the foundation with the help of trikam – instrument for hand digging. Then they made holes in stones of 2-3ft depth and inserted 20cm dia iron bars in it, which will provide sufficient strength to the dam. The slope of the body wall of the dam should be making angle of 60° with the top of the dam. The width of this top wall is kept around 1m, so that the height can be increased in future. According to the experience of Premjibhai, these circular dams are more economical than the straight ones. This is because the thin walls of the dams make it cost effective. During construction phase, various other aspects were looked into, like mixing river sand and cement and using it within short period for more strength.

Impacts of water harvesting

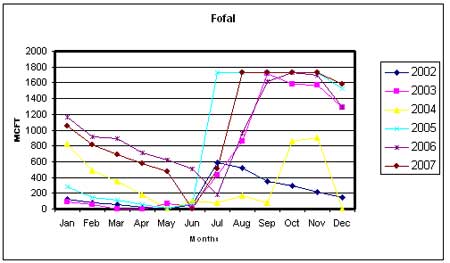

6.1 Regeneration of the river Fofal

The river Fofal, like all the other rivers in the region, was not a perennial river. Water would be available in the river only up to November. As a result of the check dam building, the river has been regenerated. Today, water is seen in the river through out year including the lean months and the river flow is observed in almost nine months. Villagers use the river water for meeting all their needs, from drinking to irrigation. Women no longer have to walk miles to get water, and are able to devote time for education and other social activities.

|

|

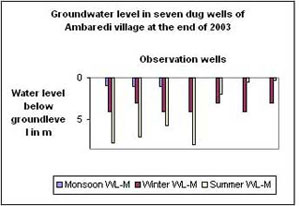

Chart: Water level in seven new dug wells at the end of 2003 |

|

|

|

| |

Map1: Check dams on Fofal river and its tributaries |

|

|

| |

Source: VPSST |

|

|

6.2 Other ecological impacts

Villages, which once looked like a desert, have now turned into green areas. An integrated approach has been made to the watershed development including wasteland development, plantation of forest species and checking of soil erosion. The construction of dams helped to increase the water level in the wells from 152.4 m to 6 m below ground level. The sarpanch of another village, Mespar, said that water is now available for 24 hours.

Phases of check

dam building

|

Total Area (Hectare)

|

Area brought under irrigation (Hectare)

|

1st batch (9 villages) |

8191.72 |

1425.88 |

2nd batch (1 village) |

800.38 |

133 |

3rd batch (7 villages) |

9116.25 |

1673.3 |

4th batch (1 village) |

764.49 |

63.44 |

5th batch (5 villages) |

6798.08 |

909.75 |

6th batch (4 villages) |

3591.05 |

900.34 |

Total |

29261.97 |

5105.71 |

| |

| Source: VPSST |

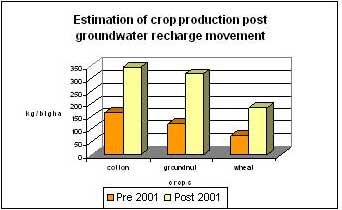

Because of the increased availability of irrigation water, the land that was lying fallow came under cultivation and the total area under farming increased from 890 hectare (ha) in 1995-96 to 22275 ha in 2006-07. More than 5000 hectares of land was brought under irrigation. Farmers began to raise three crops per year and there is no shortage of drinking water. The average yield of cotton, groundnut, wheat and chilly increased substantially. The villagers reaped a profit of 15 crore (approximately US $ 3 million) at the end 2004 from agricultural products.

| |

Chart: Increase in crop production in Ambaredi village |

|

|

| Source: VPSST |

|

As the salinity of the soil decreased, the farmers can now grow cotton in almost 80 % of the cultivated area, replacing groundnut in many fields. According to VPSST, the cotton production at the end of 2004 increased ten times in the villages under watershed project. Jerambhai Patel, chairman of Watershed Committee says that in 2003, he earned only Rs. 50,000 (US $ 1000) from cotton and groundnut crops, whereas, in 2004, after water harvesting, his income shot up to Rs. 4 lakh (Us $ 8000).

The availability of the fodder has also increased the milk production (5 litres/day to 8 litres/day) from the cattle in the area. As a result about 16,000 litres of milk is produced per day in the areas under the watershed program.

6.3 Socio-economic impacts

The ecological regeneration arising from increased availability of water has led to socio-economic and lifestyle improvements. Newly constructed houses can be seen in almost all the villages under this watershed project. Villagers have purchased tractors and constructed pucca (cement construction) houses. More than 150 families have purchased motorcycles and increase in percentage of admission in schools increased from 50 to 90 %. More numbers of girl children are being sent to school. Womenfolk now do not have to travel very far for washing, cleaning or collecting water for potable uses. Other small streams villages have appreciable water even during peak summer.

The increase in agricultural activities not only assured employment to the local people but also provided jobs to the villagers of the neighbouring areas. The villagers went back to their original profession of farming and gave up polishing of gems and jewelleries. The migration to nearby cities has completely stopped and people in the villages concentrate on farming. Today not a single inhabitant of the village depends on drought relief.

6.4 Community mobilisation

The VPSST acknowledges that local communities have an excellent knowledge of the geology, topography of the land and are thus best placed to decide on the design, height, location etc of the check dam. The role of VPSST was to secure and manage the finances and to provide training to the villages on construction technologies.

VPSST also encouraged villagers to involve themselves in the construction work. This would reduce the costs and also ensure quality of construction. Village communities, led by the sarpanch, would decide on the cost of the project, based on detailed calculations for stone, sand, cement etc. Villagers were then convinced of the genuineness of the cost estimates and contributed their share more willingly.

Initially people were not interested in the public participation for the construction of the check dams. Villagers were distrustful of government programmes and were reluctant to participate. The trust had to hold several meetings to convince the villagers that they stood to gain from the building of check dams to hold rainwater. VPSST therefore, started the movement by going ahead with the construction without any contribution from the villagers. Once the benefits of the check dams were visible to the people, they then came forward to be part of this endeavour.

By the end of 2005, the trust was successful in this movement and many farmers joined the user group for an assured source of irrigation. Due to availability of water in the river/rivulets through out year, there is no competition between the farmers for lifting

water from the water bodies. Any one, irrespective of caste and creed, can use the river water for irrigation.

6.5 Institutional framework

To ensure sustainability of this movement, it was necessary to set up participatory systems to manage, sustain and expand this effort. The VPSST helped to form village management committees called “Watershed Vikas Samiti” (Watershed Development Committee). The committee consisted of eleven members, headed by the sarpanch of the village. Villagers from the agrarian class united together to form this user group. The main work of this Samiti was the proper management and planning of check dams.

The beneficiaries decided the location for construction of check dam so that maximum water can be stored and maximum amount of water can flow in their well. The beneficiaries did all the work right from acquiring the raw materials up to supervision of construction. When a check dam was under construction, various people from the neighbouring areas were invited to learn about construction methods. Sometimes, special workers (Kadia) were called for the construction purpose.

Besides implementing the water harvesting structures, the committee used the money for well recharging, building of underground tanks, animal husbandry, planting trees and seed sowing. The committee was in charge of the maintenance of the structures.

7 Funding

The interesting feature of the work on water harvesting structures in these villages of Gondal and Jamkandorna is that the villagers constructed the dams at a lesser cost as the farmers themselves were involved in the construction and they did not hire other labour. The involvement of the farmers also ensured that there was no wastage in the use of materials. Thus, while the government funding was as per standard guidelines, the Trust was able to use the funds meant for one dam to construct two more dams. Some of the funds saved from the money provided for check dam construction were also used for the construction of underground rainwater harvesting tanks in the villages. Some 206 such tanks were constructed.

In the first phase, the money was given to any villager who approached the trust, as it was necessary to get participation from the villagers. Initially, the rich landlords from the Patel community were the first to seek the funding. The farmers were able to derive great benefits from harvesting rainwater by way of improved crop production. This helped to catalyse farmers from other villages to get involved in the check dams movement7.

8 Conclusion

The study reveals that water scarcity was the major constraints to agriculturalproductivity in the villages of Gondal and Jamkandorna talukas. Perceptible changes were observed in the villages of this region after the water harvesting movement began in 2000. There was a big improvement in the areas under irrigation, cropping pattern and

The sarpanch is the head of the village panchayat, which is official decentralized governance forum in each district.

Intensity along with diversification of crops from traditional to commercial or cash crops. The average yield of cotton, groundnut, wheat and chilly increased substantially over a period of time water storage capacity of the aquifers increased significantly, covering more area under irrigation. The water level in the wells increased from 150 m to 6 m below ground level. Water is available in the Fofal river throughout the year.

What is clear from this case study is that, this movement is more than just a water recharging activity. It has catalysed the involvement of the entire village and has resulted in many innovations and improvements. It has transformed this entire activity into a social movement, where the entire village is involved in improving their economic status by managing their natural resource base wisely. Rainwater harvesting has been shown to play an effective and a key role in improving food and livelihood security.

What should be the role of the government: It is clear from this and many other experiences that natural resource management can best be undertaken by communities who have a stake in its integrity. But is it realistic or sustainable that communities can be left to do this themselves? Many other experiences such as Ralegan Siddhi, Hiware Bazar, have shown that the government has an important role to play – but that of an enabler and not a doer. In all these cases, including this case study, the communities have taken advantage of the financial support provided by the government in order to begin the water harvesting activity and then go on to undertake wider watershed activities.

The government, while providing catalytic financial support, must ensure that the villagers participate in this activity at every step – from planning to design to funding. Only then will such projects be sustainable, as the villagers will have a sense of ownership over the project. Such a sense of ownership is crucial for the villagers to take responsibility to maintain the structures.

The government should also make available the technological resources at its disposal – for instance, by providing scientific tools such as GIS and remote sensing data and have its technical staff provide technical assistance to the villagers.

An effort has also been made to institute systems for sustainability.

Case study of Ambaredi village

Ambaredi is a village in Jamkandorna taluka, which experienced a complete changeover from dry agricultural land to lush green fields. The village is located in southwest portion of Rajkot district about 80kms from Rajkot city. River Fofal flows almost North-South through the village for about 40 km and joins the Bhadar River. There are numerous small streams connected to Fofal forming a dendritic pattern of network in the area. The soil in this area is predominantly black cotton and thus suitable for the cultivation of cotton and groundnut. Open dug wells are the main source of water and before the check dam movement, the wells used to be dry in summers. The VPSST has, till date, constructed a total of 70 check dams in Ambaredi village. |

impact

The villagers are able to raise three crops a year due to assured source of irrigation and there is no shortage of drinking water also. Groundnut and cotton are produced in the first rotation, jeera (cumin seed) and wheat in second rotation and in the third rotation onion and garlic are produced. The area under wheat cultivation had increased by 13 times at the end of 2003 . As a result, the earnings from wheat production also increased from Rs. 8, 000 (Us $ 160) to Rs. 125, 000 (Us $ 2500). The total income in the village, which came from selling of cotton, increased from Rs 1920 (Us $ 38.40) to Rs 6500 (Us $ 130) per day. Improved variety of groundnut and other seeds were also sown in the area.

|

|

Chart: Water level in Fofal River between 2002-2007 showing increase in water level due to water harvesting |

|

|

| |

Source: Gujarat State Groundwater Board

|

|

Prior to the recharging movement, the wells used to have water only during the monsoon period. At the end of 2007, all the 210 wells (200 dug wells and 10 borewells) were yielding water. The groundwater was observed at 3 m below ground level even during the lean period. The well and the surface water is enough to cater the year round and the villagers have not purchased water from the tanker suppliers for the last five years.

|

|

References

- Standing the test of drought, 2000 in Down To Earth, Society for Environmental Communications, New Delhi.

- Shamjibhai Antala 2001, The Awakening in Making Water Everybody’s Business, Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi, p 75.

- http://www.nih.ernet.in/learning.htm#Potential_Evapotranspiration_over_India

- P N Phadtare 199, Geohydrology of Gujarat State (with status of work carried out by the Central Groundwater Board up to August 1988) Gandhinagar: Government of India, unpublished.

- Premjibhai Patel, 2008, Vruksh Prem Seva Sanstha Trust, personal communication.

- Mudrakartha, S. 2008. Adaptive approaches to groundwater governance-lessons from the Saurashtra recharging movement. Institute of Rural Management, Anand. Working paper no. 204. 49 p.

|

|

| |

|