|   THE NEED THE NEED

Efficacy of environmental laws

In India, maintaining environmental balance with economic growth is a subject of

state policy. Since 1974, several environmental laws have been enacted and numerous

institutions have been set up to implement the objectives of these laws. But this

traditional form of governance –enacting a law and then setting up a bureaucracy to

implement it – has failed to reduce industrial pollution in India. Monitoring

mechanisms are often not effective because of poor availability of financial and human

resources. Enforcement mechanisms also lack teeth. Part of the reason is also that

government agencies have failed to inform the public in a way that there is a constant

debate on ways to reconcile difficult contradictions between environment and development

and thus, unleash an energy that would overtake the current inertia.

|

The bureaucracy has

failed to implement laws to reduce industrial pollution in India |

|

India is just beginning to industrialise, urbanise

and motorise, however, it is already heavily polluted and in some places probably more

than anywhere else in the world. Already most cities are suffering from severe air

pollution and many rivers, both small and big, have turned into sewers. All this will have

a serious impact on the environment and public health, reducing the quality of life,

especially in urban areas where polluting activities are concentrated.

Pollution will rise rapidly with economic growth and

reach unbearable proportions – just as it did in the industrialised countries in the

1950s and 1960s within a decade or so of the post Second World War economic boom –

unless we take specific measures to control it.

If pollution grows, there will be public protests,

and given the space that Indian democracy provides, either the politicians or the courts

will have to respond. Judicial activism, community and civil society protests are all

already beginning to bite. In such a situation, it is the industrialists who are likely to

find their investment most threatened. Therefore, for a country like India, it is in the

industry’s interest to adopt a proactive role in environmental management.

We strongly believe that with proactive action, both

economic development and environmental conservation can go hand in hand.

Foreseeable future

We can foresee incredible levels of pollution in the years to come unless some serious

efforts are made to prevent it.

Take a look at the following study done by the World

Bank in the mid-1990s: The toxicity intensity of the industrial economy – the toxic

load generated per unit of industrial output – increased 1.11 times between 1977-87

in Japan, a developed country – but increased 5.4 times in Indonesia between 1976-86,

around 3.17 times in Pakistan between 1974-84 and 3.05 times in Malaysia between 1977-87 – all developing countries.

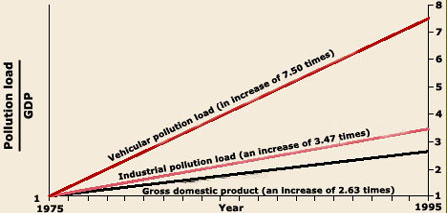

In twenty years after 1975, the gross domestic product (GDP) grew 2.6 times in India but

industrial pollution more than tripled and vehicular pollution increased by almost eight

times.

The pattern of industrialisation followed in the

developing countries clearly shows that if a country like India is going to double its

GDP, without looking at pollution control, then pollution load will increase rapidly and

disproportionately by as much as ten times.

It is, therefore, vital to avoid the

apocalyptic collision between economic growth and environment, by monitoring and

influencing the future industrialisation of India.

THE

PROJECT

The project was conceived in

the mid- 1990s when Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) director Anil Agarwal visited

the United States. He read about the work of an non-governmental organisation (NGO) called

the Council of Economic Priorities (CEP), which rated the social and environmental

performance of industries in the US. CEP then provided this information to those investors

who wanted to invest only in environmentally and socially responsible businesses. Anil

Agarwal was pleasantly surprised to learn that despite no government and legal support,

these ratings were pushing industry towards more socially and environmentally conscious

business practices. THE

PROJECT

The project was conceived in

the mid- 1990s when Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) director Anil Agarwal visited

the United States. He read about the work of an non-governmental organisation (NGO) called

the Council of Economic Priorities (CEP), which rated the social and environmental

performance of industries in the US. CEP then provided this information to those investors

who wanted to invest only in environmentally and socially responsible businesses. Anil

Agarwal was pleasantly surprised to learn that despite no government and legal support,

these ratings were pushing industry towards more socially and environmentally conscious

business practices.

|

| The pattern of industrialisation

currently followed by the developing countries is highly polluting and toxic |

|

Considering the failure of government

agencies to control the ever-rising level of pollution in India, to him, the idea to

initiate a similar exercise in India was both timely and relevant.

Preparations for the project then

began back home in early 1995. Many brainstorming sessions were held with eminent experts

from all over the country. These meetings clearly identified the urgent need to build an

alternative form of governance based on public participation, transparency,

non-bureaucratic institutions and market-oriented policies, to monitor and influence the

process of industrialisation in the country.

| Graph 1: Growth in vehicular and industrial pollution has outstripped economic

growth |

|

| Source:

GDP from Indian Economic Survey, 1997-98. Pollution load based on CSE study, 1998. |

Most of the participants felt that

the Centre for Science and Environment could start a similar industrial rating project in

India. Being a public interest organisation, catalysing action for sustainable

development, CSE was well suited as an institution to help in the development of this

alternative form of governance.

It was for the first time that an NGO

in the developing world was undertaking the environmental rating of industrial sectors. It

came to be known as the Green Rating Project (GRP).

THE BASIS THE BASIS

Unfortunately, in many developing countries like

India, policies and institutions for controlling pollution and degradation of the resource

base are weak and still in a nascent stage.

The current status of India’s environment shows

that the regulatory mechanism has failed to control industrial pollution.

Therefore, the Green Rating Project arises out of an urgent necessity to bridge the gap

between weak regulatory mechanisms of the government, on one hand, and the achievement of

sustainable development on the other.

Presenting incentives

Green Rating Project is an attempt to present a market-oriented framework by which the

environmental impacts of industrialisation can be measured and monitored.

|

| As GRP is built on

voluntary disclosure by companies. The rating system consists of both a stick and carrot

policy |

|

This is a reputational

incentive programme, which rates the environmental performance of companies within a

specific sector. The results of this research are then disseminated to a wide audience,

including investors, consumers, media and financial institutions, both within India and

abroad.

Indian industry has been freed from bureaucratic constraints, but

has, at the same time been exposed to global competition.

This drastic change in the business environment calls for an

urgent appraisal of the problems and prospects of Indian industry. At this point of time,

issues such as clean technology, global environment protection and energy conservation are

assuming greater importance and becoming the hallmark of the global business environment.

Conventional wisdom suggests that there is a conflict between the

goals of environmental protection and economic competitiveness. But proactive industry

leaders argue that this is not true as long as state policy creates a level playing field.

In fact, certain progressive firms have adopted state-of-the-art

technologies for pollution reduction but have never made their performance standards

public. These firms are not receiving any recognition for their efforts.

On the other hand, industrial segments that are lagging behind in

environmental performance do not feel any public pressure to improve. CSE strongly

believes that by projecting a transparent picture of the environmental performance of

Indian companies, poor performers will be encouraged to improve their environmental

performance.

One of the greatest assets of a company is its public image.

Greater public awareness about the social and environmental commitments of a company will

pay rich dividends in the form of product loyalty and thus provide an edge over its

competitors.

The power of public pressure can be gauged by the fact that in

last few decades all the major toxic products have been phased-out of the market not

because of the conventional command and control mechanism or by the economic instruments.

It has happened because the public has been informed about the environmental damages being

caused by these products. Banning of Di-chloro Di-phenyl Tri-chloroethane (DDT) and

intermediate dyes, push for chlorine free bleaching in paper industry, etc. have all

happened because of the public pressure.

Therefore, the reputational incentive involved in public

disclosure of ratings is the basic foundation of the Green Rating Project.

THE CHALLENGE

Several NGOs in the West today undertake the rating of the social and

environmental performance of companies. The US based NGOs use the Toxic Release Inventory

(TRI), a database carefully maintained by the US Environment Protection Agency (USEPA),

which has year-wise information on the wastes and emissions of companies and is openly

accessible to everyone. THE CHALLENGE

Several NGOs in the West today undertake the rating of the social and

environmental performance of companies. The US based NGOs use the Toxic Release Inventory

(TRI), a database carefully maintained by the US Environment Protection Agency (USEPA),

which has year-wise information on the wastes and emissions of companies and is openly

accessible to everyone.

|

| The stick is a

‘default option’ under which a company, which does not voluntarily disclose

information is rated as the worst company. The carrot is ‘additional weightage’

given to the company for transperancy |

|

Once this data is available, it is easy to

set up some benchmarks and rate them accordingly. However, it is not possible for NGOs in

India to adopt the US strategy.

In India, the Central Government does not maintain such a

centralised database and even the data that it has on companies is not easily available to

the public. In fact, different state governments have different attitudes towards public

accessibility.

Moreover, within the environmental community, there is very little

credibility in the data being supplied to the government unlike the credibility enjoyed by

USEPA’s Toxic Release Inventory.

GRP, therefore, relies heavily on voluntary disclosure by

companies and then puts the information supplied by companies through a rigorous technical

scrutiny. Voluntary disclosure of environmental performance is no longer an exceptional

exercise. On the contrary, it is becoming a hallmark of good business practice across

their own. environmental protection has been redefined as pollution prevention, from its |

![]()